|

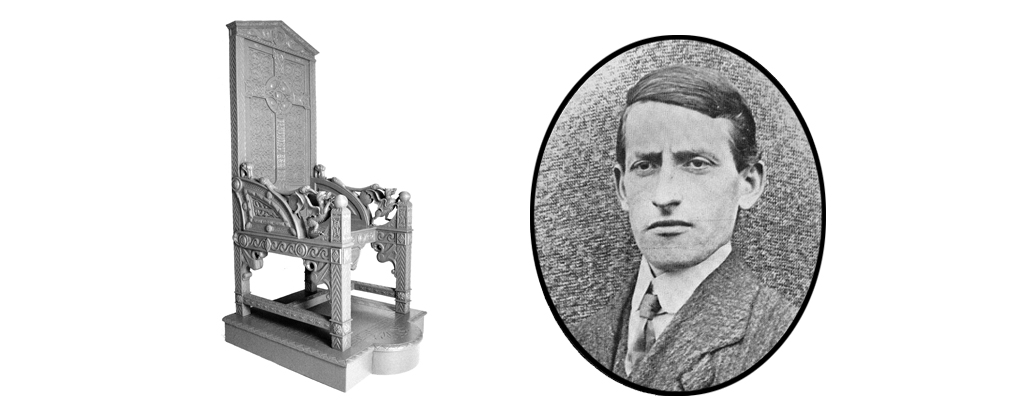

When the Archdruid asked the question, 'A oes heddwch?' ('Is there peace?'), during the chairing ceremony of the Birkenhead National Eisteddfod on September 6th, 1917 the crowd in the pavilion could hardly answer by reiterating the word ‘Heddwch’ ('Peace'). The First World War was still in full swing with the chair on the stage in front of them draped in black. When the winning poet's nom de plume, 'Fleur de Lis', was announced, no poet stood up and the crowd was informed that Ellis Humphrey Evans (Hedd Wyn) had been killed at the battle of Pilckem Ridge five weeks earlier. But there was another reason for the unease of the crowd that day - how best to respond to the war that was dragging on from one year to the next, causing thousands and thousands of deaths and how best to achieve peace? |

|

|

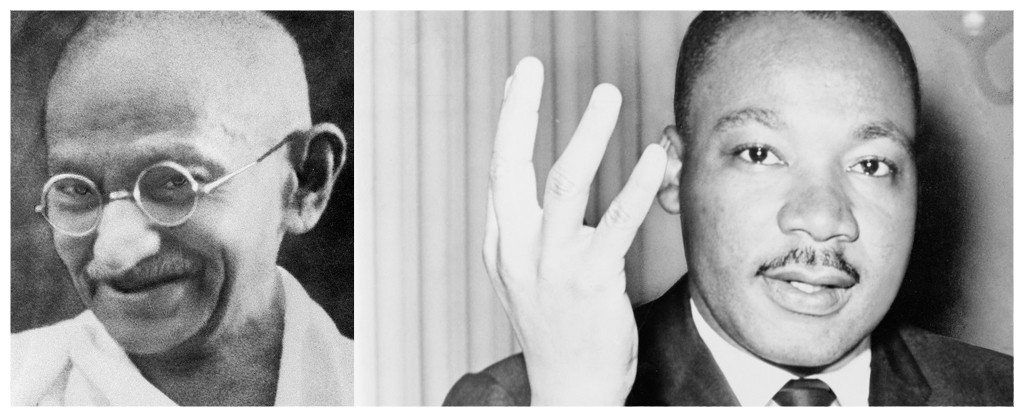

Imagine this situation. As you walk down the street you see a big bully attacking a younger and vulnerable child. You go to him and ask him to stop. He does nothing but laugh in your face and carries on. What then? There's a brick on the floor - you could lift it and hit the bully and stop the attack. You could go looking for friends to help you - some might agree to come with you, but others might refuse because they don't believe in fighting or hurting anyone, bully or not. Others might be willing to come and try to persuade the bully and you may be able to force some to help you attack the bully. While you decide what to do, the attack continues. Now escalating that situation to an international level, we see a lot of the issues and questions that arise when discussing war and peace – have I responsibility to help victims of a violent attack? Who is entitled to use violence and force others to use it? Is violence sometimes the only solution to achieving peace? These questions have puzzled religious people over the centuries. For pacifists, in all religions, the use of violence is not justified - no matter what the reason or circumstances, you cannot justify hurting or killing others. Violence only incites violence and the only way to achieve peace is by negotiating and following the non-violent path. This is the method of Gandhi and Martin Luther King - two who influenced humanity. Gandhi believed in ahimsa, the non-violent principle - “ahimsa comes from strength, and the strength from God, not man. Ahimsa is always from the inside.” Peacekeepers are not cowardly and spineless, but people who are prepared to stand up for their beliefs, no matter what happens. In the World Wars they suffered for their beliefs - despised by being called 'conscientious objector' while others were imprisoned. |

|

|

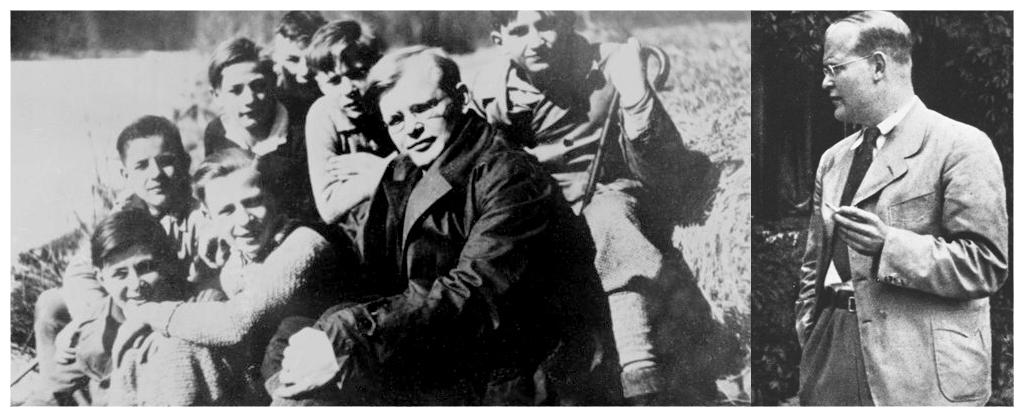

Ideally, no one wants to see war or use violence but, sometimes after trying everything, some believe that there is no other solution but to use violence. If someone is fighting for good against evil, then the violence used is justified. This can cause major dilemmas for religious people. One of those who faced such dilemma was Dietrich Bonhoeffer during World War II. Bonhoeffer was a German minister and, as a Christian, he opposed Hitler and his policies. By 1942, thousands had already died in World War II, and many Germans believed that the only way to end World War II, thereby saving thousands of other lives, was by assassinating Hitler. Bonhoeffer's dilemma was how to reconcile that with his Christian faith. Could murdering one man justify saving thousands of lives? In the end, he decided it could and he joined Colonel von Stauffenberg’s plot. The attempt failed and Bonhoeffer was arrested in April 1943 and, two years later, hanged in Flossenburg. |

|

|

In the Sikh religion there is the idea of a sipahi-saint, the soldier-saint, namely the idea that the Sikh has a duty not only to try to follow the teachings of the religion, but also to protect them in every way against any attack. Interestingly, there is a cohort of religious believers who are between the above two perspectives - a non-violent point of view, like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, and using violence like Bonhoeffer. On the one hand, they feel a duty to oppose evil and to stand up for good and are unwilling to let others take the responsibility of doing so for them. But, on the other hand, not willing to carry weapons and use violence to do so. RR Williams - author of 'Breuddwyd Cymro mewn Dillad Menthyg’ (‘The Dream of a Welshman in Borrowed Clothing') talks about the internal struggle he felt as a Christian - 'The conscience of war was not completely silenced at the time I decided to join and the hatred for it has never faded.' He is referring to the Welsh Medical Corps. At the beginning of 1916, a special Welsh unit of the Royal Army Medical Corps was formed for those who had pacifistic tendencies but who wanted to serve in the Great War without carrying weapons. Their work was difficult and dangerous - going out unprotected into the middle of the battlefield to treat the wounded soldiers or to retrieve the bodies of the slain. They witnessed horrific scenes, day after day. No wonder they returned from the war with their hatred for fighting hundredfold. |

|

|

Cynan was a member of the Medical Corps and parts of his famous poem, 'Mab y Bwythyn’ (Son of the Cottage) refer to his personal experiences in the midst of the fighting, the barbed wire, dead bodies, rats, the stench and the sound of the guns -

'O dan y gwifrau pigog geirwon However, the ones we should sympathise with most are, undoubtedly, those who were forced to fight and that is what happened to Hedd Wyn. He became a member of the army under the Military Enforcement Act of 1916. He had no desire to join the army and his poems of the period subtly suggest his hatred towards it. He could have avoided going on the grounds that he was an agricultural worker, but he went so that his younger brother didn’t have to go. He repeatedly told his girlfriend, Jini Owen "I will never shoot anybody. They can shoot me if they like.” Unfortunately, and sadly, that is what happened. Another problem facing believers is how to remember those killed in wars. The most common way of course is to buy and wear the red poppy. Yet many believe that there is too much emphasis in that remembrance of war and that there is a danger that war and participation in war are extolled. That's why some wear the white poppy and shift the emphasis of remembrance towards peace - remembering what happened in wars to make sure it doesn't happen again. When the Archdruid asks the question 'A oes Heddwch?' At this year's Anglesey National Eisteddfod, one hundred years after the death of Hedd Wyn, will it be easier for the crowd to answer by reiterating the word 'Heddwch'? |